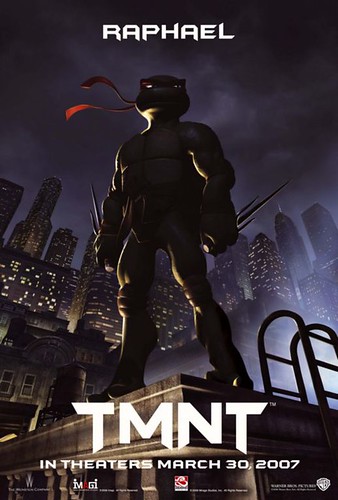

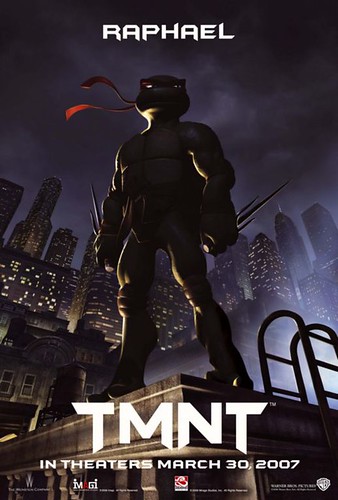

Hilarious Quote of the Day

"As a piece of film design, the movie is first-rate; on sheer aesthetics alone, it rivals Triumph of the Will for astonishments." - Stephen Hunter of the Washington Post on TMNT

Seems like an apt comparison to me...

a film blog

"As a piece of film design, the movie is first-rate; on sheer aesthetics alone, it rivals Triumph of the Will for astonishments." - Stephen Hunter of the Washington Post on TMNT

Seems like an apt comparison to me...

Superproducer Brian Grazer was recently tapped as the first "guest editor" of the L.A. Times Current opinion section. You may know Grazer as the wunderkind behind such classic cinematic masterpieces as Flightplan, Nutty Professor II: The Klumps, and pretty much every Ron Howard movie ever made.

Well, L.A.-based media blog L.A. Observed broke a story yesterday claiming that Grazer got the position because Andrés Martinez, the editorial pages editor who selected Grazer, is involved in a romantic relationship with Kelly Mullens, an executive with the PR firm representing Grazer's Imagine Entertainment. The post caused a significant amout of backlash and mudd-slinging between editors and PR personal, resulting in a whole lot of 'he said-she said' quotes that could run circles around a White House press report.

The end result? Grazer is out.

"We have an appearance and not a case of actual undue influence. We want to do the right thing for our readers and for the paper," Times publisher David Hiller added.

"We're concerned that even the appearance of a conflict is enough to discredit the hard work of reporters and editors in the newsroom," said Charles Ornstein, a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter. "This newspaper has worked very hard, even during these trying times, to consistently improve our coverage and remain upbeat about our future. To face a potential scandal is really discouraging."

A New World Pictures release 1972

Written & Directed by Ingmar Bergman

Karin (Ingrid Thulin) and Maria (Liv Ullmann) watch as their sister Agnes (Harriet Andersson) slowly and painfully passes away. Anchored by the servant Anna (Kari Sylwan), the lives of both sisters are described through flashbacks, which are full of lies, deceit, callousness, self despise, guilt and forbidden love.

Unlike most of Bergman's films, Cries and Whispers uses saturated colour, particularly crimson red. Like, a lot of crimson red. Of course, the color is used frequently by directors to highlight certain themes - Hitchcock used it often to accent psychological shock, M. Night Shyamalan used it in Sixth Sense to let us know there were dead people afoot - but Cries & Whispers is probably the most red movie of all time. The color is so intense and pervading that it's almost impossible not to associate it with the film after you've seen it.

Bergman explained the use of the color by saying, "Cries and Whispers is an exploration of the soul, and ever since childhood, I have imagined the soul to be a damp membrane in varying shades of red." Sounds a bit silly, but it works - the film is an exploration into the hearts and minds of its characters, and displays a range of complex emotions that can only be described as utterly human. Bergman is relentless in his portrayal of contrition and callousness, and the staunch red backgrounds only reinforce the blow. The slow pace may be off-putting to some, but end result is rich, rewarding cinematic experience. Worthy of repeat viewings.

A Toho Company release 1961

Directed by Akira Kurosawa

Writing credits:

Akira Kurosawa

Ryuzo Kikushima

A wandering samurai (Toshiro Mifune) enters a rural town divided between two gangsters and plays one side off against the other.

A United Artists release 1964

Directed by

Sergio Leone

Writing credits:

Ryuzo Kikushima (screenplay Yojimbo)

Akira Kurosawa (screenplay Yojimbo)

Víctor Andrés Catena (screenplay)

Jaime Comas Gil (screenplay)

Sergio Leone (screenplay)

A wandering gunfighter (Clint Eastwood) plays two rival families against each other in a town torn apart by greed, pride, and revenge.

A Fistful of Dollars is most well known as the first installment of Sergio Leone’s popular spaghetti western trilogy featuring Clint Eastwood as the nameless gunslinger. These films demythologize the traditional American western, appropriating standard genre motifs and reinventing them; shot in Spain by Italians and produced by Germans, these spaghetti westerns exist as a reflection of America the melting pot. However, Fistful is also of particular note in that it is a transcultural adaptation of Akira Kurosawa’s samurai film Yojimbo. The films share much in common, especially in regards to character and story arc, but ultimately the transitioning of genres separates the two from each other.

Yojimbo takes place in 1860, a time where samurai were beginning to be erased by a thriving middle class. The film follows a hungry ronin (Toshiro Mifune) who finds himself in a desolate town split in two by a pair of feuding gangsters. The samurai, who names himself Sanjuro Kuwabatake in film, seizes the opportunity to play sides, ultimately killing all the gangsters and making some money in the process. Similarly, Fistful of Dollars deals with a nameless character that enters a town ravaged by gangsters and follows his attempts at confounding the corrupted. Both films also feature subplots that involve the rescue of a concubine and the subsequent return to her family.

The construction of character in both Yojimbo and Fistful is very similar as well. The main protagonist in each is portrayed as a mysterious, mythologized version of their real-life equivalent. Both the samurai and the gunslinger exhibit physical abilities beyond the norm: the gunslinger is a perfect shot, the samurai a fierce, unparalleled warrior. Their clever manipulation of the gangsters mimics a god-like force, supported by the frequent elevated character placement – “Everything looks different from up high,” says the gunslinger – and use of close ups and altered perspective to make the characters appear bigger than their surroundings. Rolling boughs of fog introduce each character, and both are equated with death and ghosts at some point, reinforcing character mythologization.

It is clear that the basic details of both of these films are very similar. However, what most disrupts these similarities is the transition of genre from samurai film to western. For example, the introduction of a gun in Yojimbo is a major turning point. The gun represents a new threat, western technology and the rising middle class, and the samurai’s ability to avoid and castrate the gun supports the mythological presentation of his character. Because it’s a western, everyone in Fistful uses a gun. The threat is now about size (colt vs. rifle), and though the mythological effect remains, the symbol of the gun loses its multi-layered meaning.

Likewise, the town in Yojimbo is divided evenly into two equally powerful gangs, whereas the town in Fistful is split between the ineffective law (Sheriff Baxter and his gang) and the ruthless Rojo gang. This alteration places the feud in a different context, making the division line between good and bad seem a bit more clear. This is a definite convention of Leone’s work: though the characters are all portrayed as morally ambiguous, there still exists a sort of tiered hierarchy that allows for the sympathy of characters on multiple levels. This does not really exist in Yojimbo; the gangsters are all clearly bad, and the samurai exists as the only morally complicated character. Finally, the subplot involving the concubine and her family is anchored as a central plot device in Fistful, rather than as an effect of narrative discourse like in Yojimbo. The concubine is shown within the first few frames in Fistful of Dollars, visually alerting the audience to her condition and foreshadowing the inevitable rescue. Eastwood’s character seems fascinated by her in the film, almost as if he were about to fall in love. This foregrounding of the concubine story shifts character motivation and provides a sort of romantic element that is unexplored in Yojimbo.

Ultimately, Yojimbo and A Fistful of Dollars share much in common. However, the translation of genre provides for some very distinct changes that make Fistful its own unique film.

by

e. banks

at

9:31 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: 1961, 1964, academic, Kurosawa, Leone, revisit, samurai, spaghetti-western, Toho, United Artists