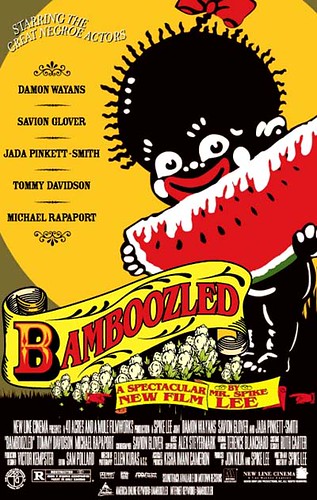

Bamboozled: Effective Criticism or Critically Underscored?

Spike Lee’s Bamboozled is a satirical attack on the way American television misrepresents African Americans. Shot in DV and converted to 35mm, Bamboozled visually reflects television as a medium, using TV’s own formal conventions to mock it as an institution. The films plot focuses on a frustrated African American TV writer named Pierre Delacroix (Daman Wayans) who proposes a satirical blackface minstrel show with hopes to reveal the mediums innate racism. Much to Delacroix’s chagrin, the show becomes a smash hit, and events unfold that culminate in a melodramatic explosion of violence. Bamboozled ultimately presents an overly sardonic, albeit somewhat accurate representation of the network television system, particularly commenting on African American participation both behind the scenes and on the screen.

The film begins with Delacroix describing the problems modern television networks face: despite offering over 900 channels with endless programs to choose from, audiences are turning away their “idiot boxes like rats fleeing from a sinking ship”. Networks, then, must come up with something new, something fresh that people have never seen before. The network in Bamboozled, named CNS, turns to their sole black head writer to come up with an ‘urban’ show that will “make headlines”.

CNS is portrayed as being an ignorant, greedy institution. Executive Programmer Thomas Dunwitty (Michael Rappaport) claims to understand what it’s like to be black because he’s married to an African woman and supports black sports stars, yet he upholds negative stereotypes such as ‘negro time’, unwittingly uses the word ‘nigger’, and ultimately is looking for a show that demeans blacks, rather than supports a dignified view. When Delacroix’s blatantly racist show is pitched, Dunwitty immediately loves it, seeing dollar signs rather than the social effects of the show’s content. He even goes so far as to edit the show according to his own narrow ideas. Similarly, the network shows little respect for black talent. Delacroix himself is often belittled by coworkers, called an ‘oreo’ for his white –catering demeanor. For a show making fun of blacks, not a single black writer is hired; the white ones who are chalk this up to a possible lack of drive, unwillingness to work for small pay, or that blacks simply “couldn’t put their crack pipes down”. Despite this lack of black writing talent, the network produces an embarrassing influx of black performers, posing the question if blacks actors are desperate for work. The network also hires a public relations expert, who comes up with a list of ways to balance the show’s racist content with positive images of African Americans, claiming “the show can’t be racist because it was written by a non-threatening black male”. Finally, the network pursues sponsors that exploit black culture, advertising products such as malt liquor and flashy clothing.

Bamboozled presents this fictional network as a reflection of real television programming institutions. Although the details are extremely exaggerated, much of what the film describes is accurate. Struggling to compete with the Internet, film, and other mediums, TV networks are now forced to find edgy, new material that pushes boundaries and grabs attention. Shows with radical sexual, violent, and racial content, like Desperate Housewives or The Shield, as well as the influx of supposed ‘reality’ based programming reflect this. Likewise, Bamboozled’s representation of blacks working in TV is rooted in fact. Currently there are very few African American writers working in the medium, and those that do exist are expected to come up with ‘hip’ and ‘urban’ concepts. The number of black performers on TV is high, but they are often found in platforms that create caricatures, rather than actual representations of African Americans. Though I doubt executives are rushing to rewrite shows to demean African Americans, the film makes a valid point about black participation within the medium. In this sense, Spike Lee’s contentions that networks do not want to see dignified blacks on the air is somewhat justified.

Delacroix’s creation, Mantan & The New Millennium Minstrel Show, is a blackface song and dance show that takes place in a watermelon patch. It gets its roots from minstrel shows, America’s most popular form of entertainment in the 19th century. Minstrel shows began in the 1830’s with white men dressing in blackface and imitating black musical and dance forms, combining savage parody of black Americans with a genuine fondness for African American cultural forms. Performers like Burt Williams and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, who often either wore blackface or catered to white audiences, clearly influenced Delacroix’s show. Mantan also finds its roots in early TV shows like Amos & Andy, which portrayed a pair of black men as bumbling, money-hungry fools. The film draws parallels between these blatantly racist forms of entertainment to more modern forms, namely the ‘gangsta’ portrayal of blacks in rap videos. The similarities are certainly there: rap videos are loved by young whites, much like minstrel shows were, and package demeaning black stereotypes as entertainment. This, coupled with the use of blackface, seem to suggest that a craze for ‘acting black’ has reached new heights with the rise of the youth hip-hop nation.

While many of these ideas are interesting, they do not exactly work within the tone of the film. Bamboozled defines satire right in the beginning as “the use of ridicule, sarcasm, or irony to expose, attack, or deride vices, follies, stupidities, abuses, etc”. Mantan works as a prime example: an obviously repugnant and humorless show that, in the real world, would stand no chance of becoming a national hit or critical success. In fact, it would never make it to the airwaves to begin with! Delacroix claims his goal is to get America to wake up to the racist content they consume. He cites the civil rights movement and it’s depiction on television as inspiration: “White America needed to see black people being beaten on the six o’clock news to promote change”. Ultimately this idea backfires, but by transforming such an overtly racist program into a ratings champion, the film argues that American TV viewers are fundamentally racist and that the entertainment industry collaborates by providing entertainment that demeans blacks. The evidence for this exists, and is humorously presented in the film first-hand through reels of historical footage and second-hand through network representation. However, the film’s preachy tone and outlandish melodrama seem to lose sight of its initial goals, and it ultimately produces the very caricatures and silly devices that Lee is rallying against. Though the point that stereotypical images continue to exist in new forms can be found, it’s hard to see Bamboozled as anything more than a rant, rather than effective criticism.

No comments:

Post a Comment